Aotearoa is a bicultural country, therefore even in projects that are not directly related to Māori communities, Māori culture and history need to be acknowledged and understood so that projects can be helpful to all members of the community, no matter what their identity. This includes understanding how the country came to be bicultural, and the colonialism that took place. In accordance with the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori are equal partners in any project in Aotearoa. Māori culture has a history of being disregarded, and students can combat this by keeping an open mind to the culture and stories they hear during interviews and while they are there.

“The fact that New Zealand is a bicultural country and that there is a treaty that recognizes Māori, Māori rights, and Māori participation in governance is huge. It means that even for our projects that don’t seem to be directly Māori related, our students need to be aware of Māori values and influences. Because New Zealand is a bicultural country and Māori are partners by treaty, their culture and values need to be understood as context for any project. Whether the project is Māori or non-Māori related, I don’t think we prepare our students with sufficient understanding of Māori history, language, and culture. For example, we do not talk much about the Treaty of Waitangi which strikes me as basic knowledge for all our students to learn when working on any project in New Zealand.”

– Professor Michael (Mike) Elmes, The Business School, Worcester Polytechnic Institute; Founder and Co-Director of the New Zealand Project Center

Taniwha and Dragon Mythology Compared

“One way that I try to gauge whether people are ready for Māori stories is to talk about a creature called taniwha. And taniwha is a mythological creature that has caused landforms to take the shape that they have. So we have a fault line named after a taniwha that caused these earthquakes and that taniwha is called Moho newi, that’s the name of the fault line. Then usually what happens is when I introduce taniwha I look for reactions and there’s a couple of reactions that happen where people freeze, so they’re trying not to show that they have any response. And then there’s others, they kind of look down and go okay, so I won’t have to listen to this for the next 5 minutes because it’s rubbish. And these are the kind of reactions that are negative. Positive ones come, take a little time to think about it.

The reason I’m bringing up that is because actually, dragons play a pretty strong role in New Zealand. And these are English stories that have come from another side of the earth up to us here in New Zealand. It’s to such an extent that we have something called the Saint George’s Cross on our flag. And the Saint George’s cross is to acknowledge something that a person named Saint George did. And what did he do? He killed a dragon. So here on one of the most very important symbols that we have is a history of a Dragon Slayer. But Māori aren’t able to talk about taniwha.

And so there’s one rule for one group and another rule for another group. The one rule in terms of Saint George comes from England, where taniwha comes from New Zealand. And so if we were accommodating mythological creatures, surely we should be accommodating New Zealand creatures as opposed to English creatures.

The hegemony is that we’re not even critically aware of the symbols that we have as New Zealanders, and then you know, we have to think about what’s happening here that some stories and some legions and some myths can go uncriticized and it can go without being hegemonic. As opposed to our native stories, is it because native stories only represent 20% of the population, where mainstream stories represent 80% of the population? So is that the democratic process producing hegemony? Can that not be? Can we not be critically aware because it strikes at the majority as opposed to even being fair and equitable?

Then, in terms of taking on Māori stories, because within Māori stories, this is the framework about how Māori think. And rather than sometimes arriving at the metaphor and investigating the metaphor for a reality, that would obviously contradict the meaning of metaphor.

Shouldn’t we be picking up metaphors and running with that in thinking, okay, so what’s meant by this?”

– Rawiri (Ra) Smith, Environment Manager (Kaiwhakahaere Taiao) for Kahungunu Ki Wairarapa; New Zealand IQP Sponsor

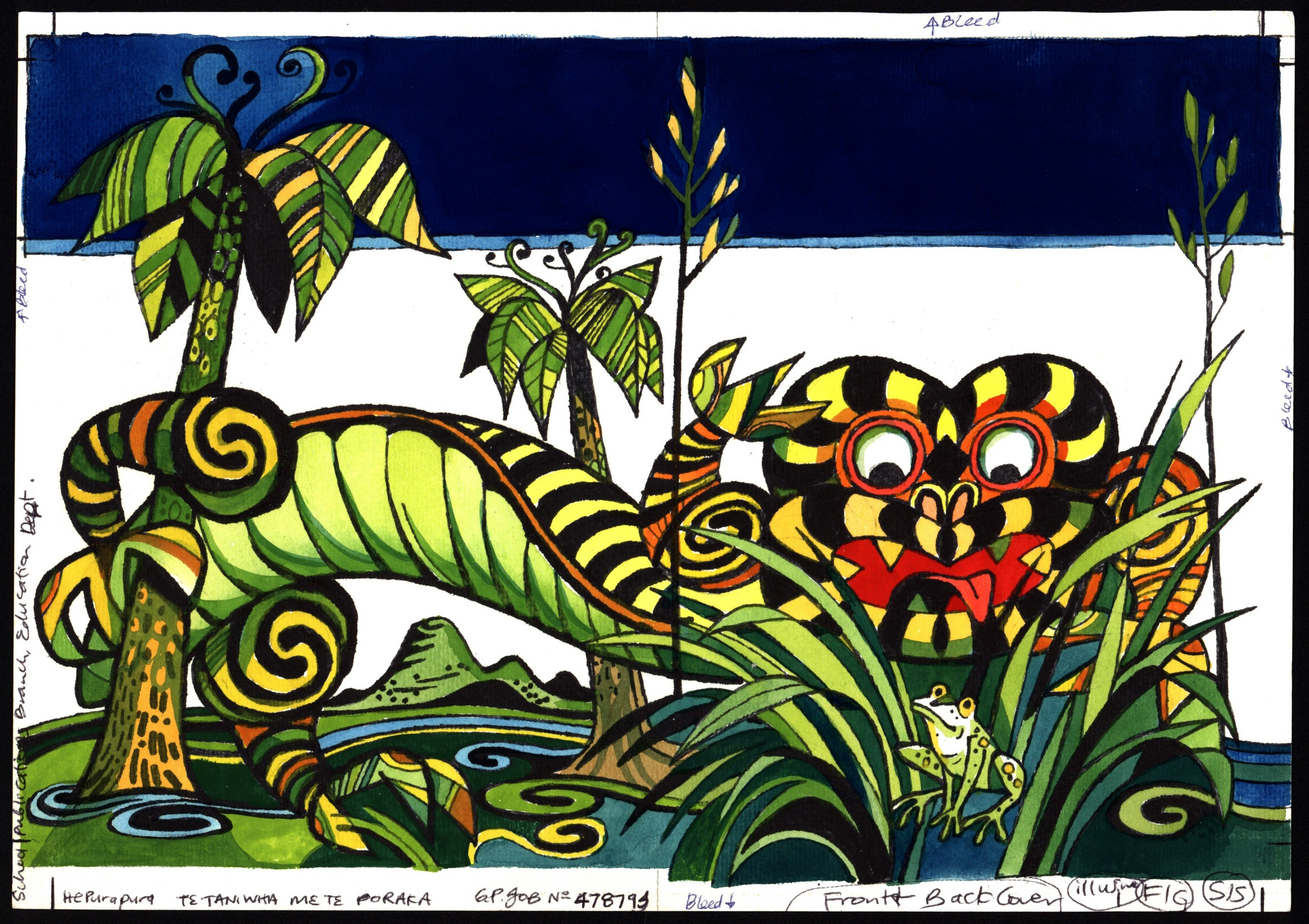

He Purapura – Te Taniwha Me Te Poraka

Murray Grimsdale, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of St. George dueling a dragon

New Zealand Flag, with the St. George cross featured in the top left corner

Ra shares an example of how Māori culture is deemed less important than western culture. He compares how the Māori story of the taniwha is treated versus the common and widely accepted western mythology of the dragon. The Māori story is treated as incorrect, while dragons, and dragon slayers like St. George, are widely accepted. The St. George cross is even featured on the New Zealand flag.

Students can combat this common disregard for Māori culture by researching it before traveling to New Zealand, respecting it, and including it in their projects.